This essay is an adaptation of a final paper I wrote for Stanford’s INTLPOL 230: Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law.

Abstract

Modernization Theory (MT) poses the idea that democracy and economic development are intractably linked, as argued by Seymour Martin Lipset and Walt Rostow, among others. Despite economic development’s material foundation-laying, there is no conclusive evidence that proves that development reliably leads to democracy, or vice versa. The nature of the state-driven development model of economics has no causal relationship with democracy. Drawing analyses from the Republic of Korea (ROK), the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and the Russian Federation (RUS), I theorize that different forms of state-driven development (SD) empirically disprove both neoclassical modernization and orthodox Marxist teleological theories of political economy.

HISTORY AND IDEOLOGY

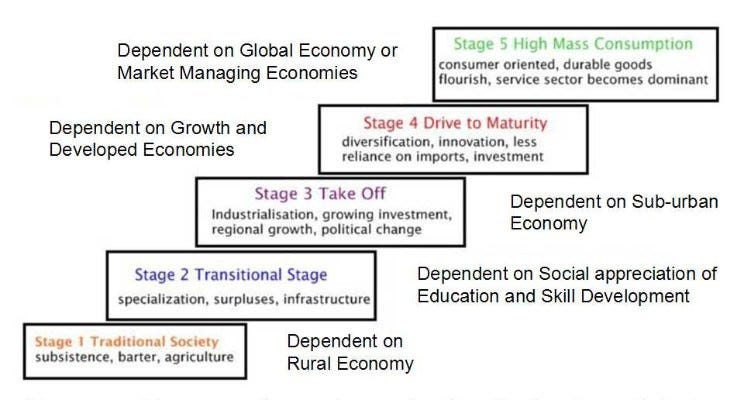

Seymour Martin Lipset summed up modernization theory as “All the various aspects of economic development—industrialization, urbanization, wealth and education—are so closely interrelated as to form one major factor which has the political correlate of democracy.” Walt Rostow expands upon this by adding 5 key stages to the development of a society: a traditional, pre-industrial society, a transitional period of industrialization, followed by a take-off period, a maturing period, and then a high-mass-consumption period, marked by a postindustrial, service-sector dominated economy. Rostow’s theory primarily focuses on a linear stage of development - that is, countries pass through all these stages consecutively before reaching an economically vibrant society that is marked by its democratic nature.

There are several issues with modernization theory from first principles: its oversimplification of economic and social change, its universalization of Eurocentric economic thought, and its focus on economic development as the primary mode of progressing a society, ignoring cultural, political, and other historical aspects in play. Krasner argues that the notion that growth is expected, sustained, and commensurate with democracy is mistaken on a fundamental level. To be clear, certain proponents of modernization theory have put forth the idea that it is not development itself that drives democratization, but rather its transformative powers upon societal norms and ideals, as well as setting the material stage for democratic “retention.”

There is further the matter of ideology that remains crucial in Modernization Theory’s history. Originally conceived by Seymour Martin Lipset, himself a Trotskyist-turned-neoconservative, it was put into practice by Walt Rostow.1 Rostow gave a structured framework to Lipset’s otherwise deterministic theories, and sought to undermine Marxist historical materialism, supplanting class conflict in classical Marxist theory with that of the conflict between nations: Marxism without Marx. Rostow sought to universalize the Western European experience with modernization, industrialization, and democracy, and was determined to craft his own “grand theory of history.”

Modernization theory’s operational history as a tool of neoconservative thought combined with both Lipset’s and the neoconservative movement’s Trotskyist past draws an interesting picture. At the core of Trotskyist thought, its main deviation from Stalinism, is its theory of permanent revolution — a key Leninist holdover that Francis Fukuyama later decried as being central to the idea of neoconservatism:

“In the formulation of the scholar Ken Jowitt, the neoconservative position[…]was, by contrast, Leninist; they believed that history can be pushed along with the right application of power and will. Leninism was a tragedy in its Bolshevik version, and it has returned as farce when practiced by the United States.”

Rostow’s characterization of his theory explicitly as a “Non-Communist Manifesto” reflects the ideological roots that were left over from Lipset — permanent revolutions, but rather than spreading communism, liberal democracy. As Krasner puts it:

Modernization theory…offered a direct challenge to Marxism. Both were teleological explanations of development. Both envisioned unidirectional movement toward a political, economic, and social order that would fulfill the highest aspirations of human beings…Once the wheels of history began turning, whether as a result of Marx’s dialectic or as the consequences of technological change and population growth, there could only be one end point: either the communist ideal society of free and associated producers or a polity in which individuals enjoyed the benefits of democracy and a market economy.

With that being said, both Marxist and non-Marxist materialist conceptions of political economy agree that so long as the material nature of a society remains relatively poor and the concerns of the citizenry primarily focus on subsistence living, the groundwork for any kind of political development beyond feudalism remains impossible.

I look to Amartya Sen’s idea of “development as freedom.” Development, Sen argues, is freedom insofar as it allows for people to escape from traditional “unfreedoms”: hunger, poverty, health care, lack of education, laying the foundations for future political participation. Yet, on the question of democratic vs. authoritarian approaches to economic development, in response to the Singaporean model, Sen writes:

“There is little evidence that authoritarian politics actually helps economic growth. Indeed, the empirical evidence very strongly suggests that economic growth is more a matter of a friendlier economic system than a harsher political system.”

Of course, while authoritarian politics themselves do not create economic development, they do not necessarily need to be divorced from economic liberalization, as we will see as we discuss South Korea and China.

SOUTH KOREA

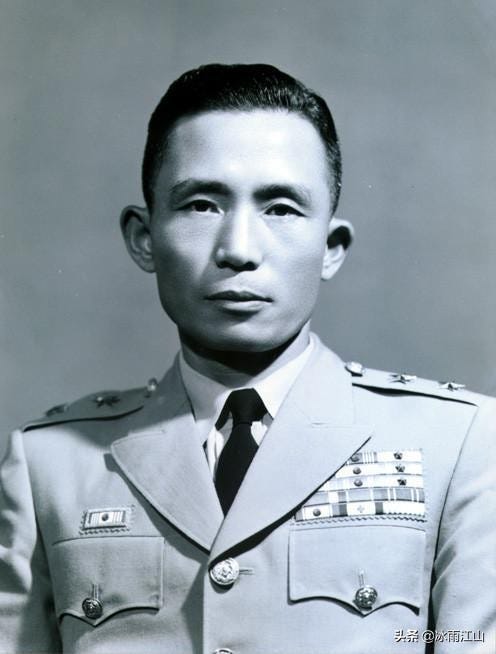

Rostowian theory found some gravitas in the South Korean dictatorship of General Park Chung-Hee, with economists in the Park regime as well as Park himself taking particular interest in the take-off period of Rostow’s theory, and sought to maximize productive forces towards achieving that stage. To this end, Park sought the help of the chaebols, family-owned businesses not dissimilar to the Japanese zaibatsu that had dominated the Korean Peninsula during the Japanese Empire’s colonization. Park’s economic policies under the Third and Fourth Republics were marked by its economic planning and consolidation of the chaebols to cooperate with the government in a form of directed state capitalism. The resulting economic success, known as the Miracle on the Han River, allowed him to gain massive popular support and performance legitimacy.

Park’s regime was characterized by its severe repression against dissidents, an empowerment of a siloviki-esque clique consisting of military, intelligence, and police chiefs, close ties with chaebol leaders, corruption and high economic growth. This is a phenomenon described by David Treisman as a “silovarchy,” a portmanteau of silovik and oligarchy. The Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA), a creation of the Revolutionary Military Committee that Park had used to seize power, held unchecked power during this time and was used often to suppress challenges to Park’s power: engaging in systemic repression against democratization movements, kidnapping political opponents, and instilling a culture of pervasive fear.

When pressed on the subject of democracy in South Korea, Park argued that “Western-style liberal democracy was not suitable for South Korea because of its still-developing economy.” His Yushin Constitution was the peak of what he termed “Korean-style democracy,” with a singularly empowered President. Yet democratization movements, termed minjung (mass movement of the people), still pulsed and chafed under the repression of the Park regime, spilling into outright protests during the Busan-Masan Uprisings in 1979, and were ultimately suppressed with the enactment of martial law. Six days following the quelling of the uprisings, Park Chung-hee was assassinated, and a military junta seized power, led by Chun Doo-hwan, establishing the Fifth Republic.

The turbulence left in the wake of Park’s assassination sent shockwaves throughout Korean society. Democratization movements that had been suppressed under the Park administration resurfaced in the power vacuum with a fury, and the military government under Chun Doo-hwan’s Fifth Republic did not understand how to peacefully respond to dissent. The Gwangju Uprising in May of 1980 was the apotheosis of these collective minjung reform movements: martial law repeal, democratization, human rights, minimum wage, and press freedom. It was violently suppressed with the enactment of nationwide martial law and the deployment of military special forces, but it severely damaged any legitimacy the Chun government had left, and would eventually lead to its downfall.

The Fifth Republic, a still-authoritarian one-party state under the newly established Democratic Justice Party (DJP), was not to last. It could be classed as a “competitive authoritarian regime” via Levitsky and Way’s definition. The 1981 re-election of Chun Doo-hwan serves as a potent case study. Chun had jailed all other prominent opposition leaders, including future presidents Kim Young-Sam and Kim Dae-jung, both members of the opposition New Democratic Party (NDP), despite amending the Constitution to allow opposition candidates.

An electoral college was still the main vehicle through which election decisions were made, and the governing DJP held an overwhelming supermajority of delegates — all but ensuring the DJP delegate would win. The KCIA, re-christened the ANSP (Agency for National Security Planning), retained its sweeping intelligence and secret police roles, providing a chilling effect on opposition movements, and the Korean media was largely restricted by the Basic Press Law of 1980, which legalized press censorship, subordinating it to the discretion of intelligence officials.

In this context, when Roh Tae-woo was nominated as the DJP nominee for President in 1987, the South Korean people reacted with fury, taking to the streets once more as they had in 1980. Chun issued orders to mobilize the Army to deal with the protestors, but, fearing a repeat of the bloody lessons of the Gwangju Uprising, he belayed them within hours. Within a few weeks of the demonstrations in what was to be known as the June Democratic Struggle, Roh Tae-woo issued the June 29 Declaration. It acceded to the protestors’ demands for direct, genuinely competitive elections for the Presidency, amnesty for political protesters, restoration of freedom of the press, extension of the right of habeas corpus, and social reform. Roh would go on to become South Korea’s first legitimately democratically elected president, setting a precedent of democratic norms that his successors would expand upon.

The productive forces that allowed for South Korea’s ascendant rise lay material foundations that allowed for the country to raise itself to a higher standard of living, but it not only no causal relationship upon the country’s rise to democracy, it in fact subordinated and suppressed it in favor of a strong centralized state, until the actions of a few uniquely empowered individuals broke with tradition. South Korea followed what Gilman might describe as the “authoritarian” flavor of modernism, which allowed it to embark on modernization without democracy. State directed development was a key divergent point in the Third World, especially when posed against traditional European modes of economic development, and were not wholly causal to democracy.

CHINA

The People’s Republic of China was officially founded in 1959 at the conclusion of the Chinese Civil War. Its first attempts at mass industrialization in line with the Marxist conception of materialist progression, the Great Leap Forward, ended in disaster. Almost Lysenkoist in its reasoning, the campaign sought two things: to industrialize by increasing steel production, and to increase grain production — both to be done by a mass mobilization of the peasantry rather than through technocratically guided industry.

A key problem that occurs in wholly command economies undergirded by authoritarian governance that uses only the stick without utilizing the carrot is that it suffers from a uniquely bad variant of the principal-agent problem. Shortfalls in skilled industrial labor led to agricultural workers being reallocated to making low-quality pig iron in backyard furnaces, and actual Lysenkoist-derived theories were put into practice with close-cropping, resulting in lower crop yields. This did not stop local officials from inflating numbers and passing said information on to the Party — resulting in disastrous public policy, and an “illusion of superabundance,” where the Party thought it had far more resources than it did. Yet this was not to last.

Walder notes in Bending the Arc that the Cultural Revolution tore down any established interests that existed, preventing them from entrenching themselves into society and hindering progress the way that the nomenklatura did in the Soviet Union. Further, the purging of technocratic officials to the countryside and rehabilitating them rejuvenated them with a vigorous work ethic and a gratefulness to be able to be returned to public service again. This groundwork, combined with the death of Mao Zedong, the downfall of the Gang of Four, and the ascendant rise of Deng Xiaoping and the reformist clique allowed for Chinese dynamism to flourish economically in the late 1970s.

However, this was a dynamism solely on the economic spectrum. The social chaos wrought by the Cultural Revolution paved the way for change, but more than anything, the Chinese people and the Party yearned for stability, which they viewed as an enforced prerequisite to a moderately prosperous society (xiaokang), proposed by Deng Xiaoping. Yet in the process of its economic reforms, relationships with the West were opened up, and democracy movements began gaining strength. Deng even considered political reforms to complement China’s economic revitalization, and reformists occupied high posts in government: among them were Zhao Ziyang, Party General Secretary and Hu Qili, First Secretary of the Party Secretariat. Both were Politburo Standing Committee members.

All these factors painted a rosy picture for a redemption of Rostow’s theory. Yet on June 4th, the Party chose neo-authoritarian economic growth over liberal democratic reforms, cracking down on the Tiananmen Square demonstrations and arresting, exiling, and imprisoning reformers, systematically purging them from government. Part and parcel of this, Minxin Pei describes, is due to the coalition of government that reigned after Mao’s death consisted of three camps: the liberal reformists, led by General Secretary Hu Yaobang, moderate technocrats, and conservatives. Deng Xiaoping acted as a moderating force between the three, and when push came to shove, he sided with the conservatives twice — first crushing student-led demonstrations in 1986, and then again on that fateful day in 1989.

RUSSIA

It is impossible to discuss the modern Russian Federation without a brief coverage of the Soviet Union, so we will do so. The economic conditions of the then-Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) in the immediate post-Civil War were mostly agrarian, backwards, and extremely poor. Despite adopting Marxist-Leninist thought, the Bolshevik leaders realized that the country had not sufficiently met the tertiary stage of material and industrial development that laid the foundational requirements for socialism, then Communism. Lenin’s aphorism that communism was Soviet power plus electrification of the entire country embodied this sentiment of the Communist Party.

From 1945 onward, the Soviet Union was the second largest economy in the world, a rapidly industrialized country rising from an agrarian backwater. The Party was stronger than ever, having come victorious from the Great Patriotic War and gaining increasing credibility for raising living standards amidst the Khrushchev Thaw, building nuclear weapons, and putting the first man in space.2 Yet this, as Walder has argued, caused stagnation and a sense of complacency among the elites that ran the productive forces of the Soviet machine.

The combination of a dependency on oil exports with the aging and dying gerontocracy among those same elites made the Soviet economy particularly inflexible and vulnerable to price volatility shocks — which is precisely what happened during the OPEC oil shocks. The economic fallout from the oil crisis, among others, accelerated the demise of the Union. The political-bureaucratic situation was no better, full of apparatchiks that jealously guarded their domains and resisted any type of progress that was deemed able to make them redundant, which was to say, all progress. The Gorbachev reforms, a reaction to the Brezhnev stagnation, itself a reaction from the Khruschev reforms to Lenin’s legacy, came too little, too late. From Ilyich to Ilyich, and from Sergeyevich to Sergeyevich, Soviet history seemed to be one of continuous tragedy.3

Post-Soviet Russia

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin was elected to the Presidency of the Russian Federation, the recognized successor state to the USSR, and immediately began a campaign of shock therapy to put Russia on the path towards liberal capitalism, with some democratic trappings. The economic situation in 1990 and 1991 put Russia on its knees. Yeltsin’s presidency, while an international embarrassment to many Russians, genuinely did try and aspire towards change on both axes — neoliberal shock therapy, rapid privatization, and price reform, coupled with regular, free, and multiparty elections.

For all its faults, Yeltsin’s government was the first genuine attempt towards a free, fair, and open democratic system in the post-Soviet states. But it could not have come at a worse time. Putin’s ascendant rise came at a time of chaos in the Federation. The 1998 apartment bombings and the Second Chechen War set the scene for Putin — once a Chekist, always a Chekist — to push a law-and-order authoritarian image that many Russians sought security from in hard times, both economic and political. His handling of the war and domestic terrorism, coupled with economic growth in Russia during his terms, gave him immense popularity in Russia.

Yet, as McFaul and Stoner argue, the rise of Putinism had little to do with economic growth. Prime Minister Yevgeny Primakov’s center-left government, appointed in 1998 in the wake of the Russian economic collapse, laid the foundational groundwork for Russian economic recovery by pursuing a thorough austerity policy that raised interest rates, cut government spending, and privatized heavily. Booming oil prices from 2003-2008 provided a much-needed windfall to the Putin government, giving the illusion of steady economic growth and development, while it fell victim to the same time of resource trap that had enveloped the Soviet Union decades before. But Putinism and its adherents did not cause this resource-driven economic boom: if anything, it seems as though they blundered their way into success.

Putin’s emphasis on authoritarianism stemmed not from an ultimate desire to preserve the state, but rather to centralize his own personal power. Stoner and McFaul note that Putin whittled away at the autonomy of regional governments —culminating in his direct appointment of regional governors — and the parliament, while simultaneously playing up internal and external threats, shutting down NGOs, and warning of a Western conspiracy to undermine Russian power in order to embolden the security state. There was no causal relationship between increased political and economic authoritarianism, but rather a directly negative one.

The Putinist approach to state-driven development (SD) should not be mistaken for the other forms of SD we have observed in our prior case studies in South Korea and China. Where Park Chung-Hee’s SD also suffered from cronyism and oligarchical attitudes from the chaebol, Park was able to use his influence to keep them all on the same page and pursued an aggressive industrial policy, rapidly shifting funds from successful industries to nurture growing ones, engaging in protectionist trade policies, and generally minimizing rent-seeking and resource-dependent sources of economic growth. Deng Xiaoping inherited a broken state, like Putin had, but the “brokenness” of both states varied immensely, and in entirely different contexts. More importantly, the rise of the Chinese economy was burgeoned immensely by the usage of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in the People’s Republic, to include Shenzhen (high tech), Hong Kong (finance), and Macau (luxury goods, gambling), which provided far more economic latitude and autonomy, rule of law, property rights, and exchange markets with Western business, rather than through sheer state-driven industry.

Conclusion

The function of development, in both political and economic dimensions, is to improve the lives of the people in the region in which it is implemented. The relationship between that of democracy and economic development is a contentious one, but one that ultimately is not one of causality.

We observed in South Korea an authoritarian, paternalistic state-driven development that created modernism, but did not have direct causal effects on the democratization of the country, which was fought for by grassroots activists. In China, the Communist Party’s economic reforms coupled with its simultaneous crackdown on political reforms — reforms inspired by ideas propagated through universities and by students, key aspects of modernist thought — runs directly counter to the idea of a causal relationship between purely development and democracy.

Post-Soviet Russia discarded state socialism for neoliberal shock therapy and rapidly privatized, spurring uneven economic growth and centralizing the majority of wealth in the hands of a few oligarchs, combined with the 2008 economic downturn and the Crimean Wars, created economic, political, and social conditions that were ripe for an authoritarian figure like Putin. Interestingly enough, Russia is actually a good argument for modernization theory: had the economy been relatively stable and the developmental level of the country remained even the same, the rise of anti-democrats like Putin would not have been necessary to step in and create order from perceived chaos.

While functional, institutionalized democratic political institutions backed by a capable state coupled with a strong mixed-market economic policy seem to be the ideal, the accomplishment of one is not a confirmation of the other.

We observe in both successful and failed transitions alike that the actual critical determinants to democratization or lack thereof lies often in the hands of a select few powerful people: Roh Tae-Woo in South Korea, Deng Xiaoping and the conservative wing of the Politburo in China, and Vladimir Putin, the siloviki, and oligarchs in post-Soviet Russia. With that in mind, history seems to reject deterministic theories, both Marxist and non-Marxist. Gone is the day of teleological grand theories — now is the time for thoughtful, specialized political economy on a state-by-state basis.

References:

Lipset, Seymour Martin (1963). Political Man. p. 41.

Milne, David (2008). America's Rasputin: Walt Rostow and the Vietnam War. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-374-10386-6.

Rostow, W. W. (1959). The Stages of Economic Growth. The Economic History Review, 12(1), p. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/2591077

Peerenboom, Randall (2008). China Modernizes: Threat to the West or Model for the Rest?. p. 63. ISBN: 978-0-199-22612-2

Jesús Velasco G. (2004). Seymour Martin Lipset: Life and Work. The Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie, 29(4), p. 583–601. https://doi.org/10.2307/3654712

Fukuyama, Francis. (2006) “After Neoconservatism.” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/19/magazine/after-neoconservatism.html

Sen, Amartya (1999) "Development as Freedom"

Lee, Steven High. (2006) “Korea's Twentieth Century Transformation.” Taylor & Francis, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/oa-edit/10.4324/9780203968277-7/introduction-korea-twentieth-century-transformation-steven-hugh-lee

Baker, Edward J. (2014) “Kim Dae-Jung's Role in the Democratization of South Korea.” Association for Asian Studies, https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/kim-dae-jungs-role-in-the-democratization-of-south-korea/

Treisman, Daniel (2007) “Putin’s Silovarchs.” UCLA, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222063024_Putin's_Silovarchs

Hyung-A, Kim. (1995) “Minjung Socioeconomic Responses to State-Led Industrialization.” South Korea’s Minjung Movement: The Culture and Politics of Dissidence, University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 39–60. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wr0rk

Sin, D. C. (1999) “Mass Politics and Culture in Democratizing Korea.” Cambridge University Press.

Yang, Dali L. (1996). “Calamity and Reform in China: State, Rural Society, and Institutional Change Since the Great Leap Famine.” Stanford University Press.

Zickel, Raymond E (1991) “Soviet Union: a country study.” Library Of Congress. Federal Research Division, Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/90025756/

Walder, Andrew (2016) “Bending the Arc of Chinese History: The Cultural Revolution’s Paradoxical Legacy.” Stanford University Press.

Pei, Minxin. (2008) “China: The Doomed Transitional Moment of 1989”

Stoner, Kathryn. (2020) “Russia Resurrected.” Stanford University Press.

Stoner-Weiss, Kathryn & McFaul, Michael. (2008) “The Myth of the Authoritarian Model: How Putin’s Crackdown Holds Russia Back.” Foreign Affairs.

See Jesus Velasco (2004), pp. 1-5 examines Lipset’s early activism in the Trotskyist Young People’s Socialist League, and later chapters detail his turn away from Marxism.

This is an enormously abbreviated and shortened history of the Soviet political economy that leaves out a lot of crucial details, and I regret not being able to write more about it.

[Vladimir] Ilyich [Lenin] to [Leonid] Ilyich [Brezhnev] and [Nikita] Sergeyevich [Khruschev] to [Mikhail] Sergeyevich [Gorbachev], a play on an old Soviet saying of Anastas Mikoyan: “от илыич до илыич без инфаркта и паралича”